I am going to write a few essays giving my thoughts as to how we return to a functioning drug regulatory system capable of protecting the public.

Last week I was at an inquest where Moderna and the MHRA had sent barristers. The Moderna barrister did a thorough job of trying to prevent me from speaking at all and then to undermine my expertise and tear apart my analysis. That was to be expected and is all part of the process of truth seeking.

However, the MHRA barrister also petitioned that I should not be allowed to give evidence. His main point was that I had relied on case reports of post mortems in my evidence. I had. Many of them. He claimed this was the lowest form of medical evidence, fundamentally failing to understand that investigation of death can only be done by looking at series of case reports are animal studies (which I also included). The usual hierarchy of experimental evidence with various tiers of clinical trials cannot apply to studying death!

The fact the MHRA was making the same arguments as Moderna struck me as perverse. The MHRA ought to be the drug police force. They ought to be interested in inquests but only as an evidence gathering exercise. They ought to be helping injured and bereaved parties prosecute the pharmaceutical companies. Instead, they have cause to defend their approval decisions. That creates a huge difficulty that different wording could solve.

First we need to diagnose the problems. In my view these are the key issues:

“Approving” drugs

Failure to monitor safety in enough detail

Regulatory employees with an eye on pharmaceutical jobs

Funding

Here I am just going to address the first.

Why is approving drugs a problem?

The term "approval" in common parlance is an endorsement. Interestingly, even the MHRA advises that companies should not promote their products as "approved" in advertising because it could mislead consumers. Yet, the MHRA itself uses "approval" when describing the temporary authorization of products like Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Moderna vaccines.

The UK drug regulator (the MHRA) themselves acknowledge the issues with this word in their own guidance saying,

“Advertisers should not suggest that their product is 'special' or different from or better than other medicines because it has been granted a marketing authorisation or registration. Nor should an advertisement state that a product has MHRA or Department of Health and Social Care ‘approval.’”

If the MHRA do not want others saying they have approved a drug, why do they use that word? There is no mention of the word “approval” in UK legislation or regulations. The term is an American one that has been adopted here with a claim that it is an international terminology.

The word “authorisation” is not much better in terms of endorsement and I would argue this word needs to go too.

Conflict

The fundamental problem we have is that the drug regulator’s purpose is conflicted (in their own words) their role is “ensuring that medicines and medical devices work, and are acceptably safe. Its work is underpinned by robust and fact-based judgements to ensure that the benefits to patients and the public justify the risks.” By muddying the waters in trying to include benefits when assessing risk, major risks can be overlooked. It is like having a justice system that balances whether the benefits to society of a particular individual being free outweigh their risks to the public. Society is best served when those charged with protecting the public focus only on that.

MHRA also recognise their own conflict in approving and then being responsible for safety. They split the departments accordingly claiming that creates independence.

The words approve and authorise really only mean that a drug has passed preliminary safety testing. Why not just say that? The only argument I can see for not rewording it like this comes down to harm to pharmaceutical companies of not having the endorsement of approval.

Benefits vs Risks

There was a time when drug regulators only had a role in banning unsafe medications. The idea of approving drugs for use came in from 1962, in the wake of Thalidomide, in USA. Unlike other safety regulators, the drug regulators deal with products that do cause harm. In their words, “all medicines have the potential for side effects and no medicine is completely risk-free as individual patients respond differently to treatment.” There therefore has to be a balance between benefits and risks when deciding whether a drug should be used. I am strongly of the view that that decision should not rest with a regulator but with the doctor and patient themselves.

The UK already has a body charged with assessing the benefits of drugs - NICE. Their output is worded in terms of economics but in order to reach those conclusions they need to calculate a “number needed to treat” for one person to benefit. There should be a responsiblity on them to give estimates for that figure based on medical condition and other variables relevant to the situation e.g. age.

Communicating risk

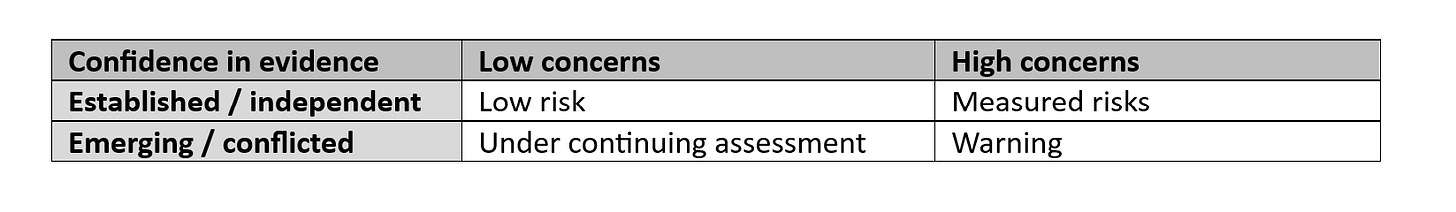

The MHRA should focus on far more careful use of language. A graded system of drug safety could easily be used based on the strength, longevity and independence of the evidence base against the seriousness of the risks.

Where risks have been measured they should be conveyed as a “number needed to harm” broken down by the seriousness of the adverse event and relevant subgroupings e.g. age.

With both a “number needed to treat” and a “number needed to harm,” patients and doctors would have access to information that could allow them to make a meaningful decision for the circumstances of that particular patient. A drug that might be considered too dangerous in the majority of the population because of a higher mortality after 10 years might be perfectly acceptable for a patient who has only a few years of life remaining.

There would still be a role in preventing certain drugs from coming to market at all and withdrawing dangerous drugs. However, the emphasis will be on clear communication of risks. There would be no endorsements.

Purpose of the regulator

The many problems with the regulator have been diagnosed by Baroness Cumberledge in a July 2021 report, indluding“The healthcare system…is disjointed, siloed, unresponsive and defensive. It does not adequately recognize that patients are its raison d’être… We heard about the failure of the system to acknowledge when things go wrong for fear of blame and litigation. There is an institutional and professional resistance to changing practice even in the face of mounting safety concerns.”

Suggested improvements included “a strengthened legal framework for safety based regulatory decision-making. In our view when a medical device or medicine safety issue is raised the MHRA should be subject to binding timescales for decisions on risk management… There should be greater transparency of all regulatory safety decisions. Regulatory decisions should be published together with the fullest possible supporting evidence.”

A Patient Safety Commissioner to represent harmed patients has been introduced in response to her recommendations. This fails to address the key point. The MHRA is meant to be the public body that prevents harm to patients from drugs. They are failing in that job. That needs to be fixed.

Worse, the CEO of the MHRA, June Raine, has openly presented her intention of turning the regulator from a watchdog to an enabler. There is no point having a regulator that sees themselves as an enabler of the pharmaceutical industry. We might as well not have a regulator at all.

It is time to give the UK public back what they deserve - a watchdog regulator charged with minimising harm from drugs.

Thanks for this. Inquests are so important. This line in particular:

"The fact the MHRA was making the same arguments as Moderna struck me as perverse."

Excellent, and impressed by all your efforts. Its unacceptable that narrative believers and government bodies get away with the phrase that serious side effects of the mRNA 'vaccines' are 'rare'. Still this phrase is used to silence the damage that was done.